The University of Cape Town (UCT) Works of Art Collection encompasses works of all art forms including, but not limited to, paintings, photographs, drawings, fibre or textile art, prints, statues and sculptures. The artworks include works from about 700 artists acquired by the University and formally accepted into the Collection.

The Collection comprises artworks that have been acquired and received through donations, loans and commissions. There are currently over 1400 artworks distributed in 70 buildings around six campuses of UCT: Hiddingh Campus, Upper, Middle and Lower Campus, Health Sciences Campus as well as Breakwater Campus.

Discover selected artworks of the Collection by clicking on the thumbnails below. Explore each piece individually or view the selection by scrolling down the page.

Unathi Mkonto

South African, born 1982

Out building, 2024. Plywood, unique, 130 x 120 cm. Acquired 2025

Unathi Mkonto views his sculptures as abstract reflections of buildings. His sculptures are imaginary architectural drawings that have become three-dimensional. In being three-dimensional, the sculptures have different sections that can be read as ‘inside’ and ‘outside’, with separate volumes, spaces and levels. For the artist, this echoes the inside and outside of buildings, and the separate rooms, staircases, passageways and balconies of architecture.

We spend most of our lives in buildings and yet seldom think of how these buildings structure our lives, with each room having specific functions. By creating a sculpture inspired by architecture, Mkonto makes us aware of how our lives are structured by and around the built environment.

Ni-shaat Bardien

South African, born 2002

Untitled, 2024. Cyanotype on paper and fabric, crochet elements, unique, 73 x 75 cm. Acquired 2025

“This Cyanotype collage combines imagery from Bokaap with imagery from my inherited Cape Malay recipe books. Adding textures and patterns from items of clothing passed down from my grandmother. The collage represents my Cape Malay heritage and growing up in Mitchells Plain. The text above reads 'Bokaap', while the bottom reads 'Mitchells Plain'. The collage is a visual representation of how I move between these two spaces. Considering that my parents were removed from Bokaap to Mitchells Plain.” (text by the artist, 2024).

Balekane Legoabe

South African, born 1995

Magicman, 2024. Digital print on archival paper, 1 of 3, 120 x 200 cm. Acquired 2025

Balekane's work explores the relationship between nature, spirituality and identity through the interrogation of personal and collective histories. She is interested in the ways in which the human experience mirrors the processes of nature and vice versa. In her dream-like artwork, Balekane draws visual inspiration from ancient rock art and cave paintings.

Mikhailia Petersen

South African, born 1992

Towards the sun, 2024. Pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, 135 x 110 cm. Acquired 2025

Towards the light forms part of a photographic series titled Reimagining Themba – a project in celebration of resilience and human spirit, created in collaboration with Little Lions Child Coaching, a Cape Town-based NGO that fosters mental health initiatives in under-resourced communities.

The collaboration held at its centre the fictional children’s story of Themba: the lion who lost his mane. Themba’s pursuit of his mane takes him on an adventure where he meets many friends who help him discover, mane or not, the qualities he possesses.

The artist, along with twelve young mentees from the Little Lions programme, embarked on a transformative journey of imagination and self-discovery. The resulting photographic series transcends the boundaries of mere imagery, weaving together narratives of resilience, courage and joy.

For Petersen, this series of photographs is a deeply personal journey informed by her own experiences with mental health stigma. The series invites viewers to reflect on the transformative potential of storytelling, community and hope.

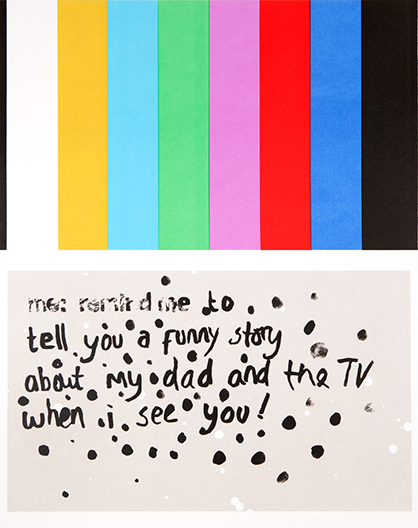

Dineo Seshee Bopape

South African, born 1981

Chat-Scat, 2024. Silkscreen print on archival cotton-rag paper, 4 of 25, 66 x 50.5 cm. Acquired 2024

‘My work is a negotiation of love, hate, mistakes, intentions, tensions, passion, intensity, boredom and frustrations. I converse with today and yesterday, as they negotiate spaces in consciousness. The result is almost always fragmentary/ fragmented.’ (Bopape in: The eclipse will not be visible to the naked eye, 2010).

Bopape’s artworks are a gathering of choices that play off each other, constructing and dismantling each other’s meanings. The images, texts and objects she uses become a cacophony of small stories, mundanities and language fragments that are both discordant and create a hint of a new kind of story-telling. In Chat-Scat, Bopape uses the television test pattern and a quote from an online chat forum to explore the banality of ordinary objects and moments whilst simultaneously pointing at the ubiquity of technology and, at the same time, suggesting that this technology is intimately part of her own personal history.

Nonzuzo Gxekwa

South African, born 1981

Blanket, 2015. Archival inkjet print on enhanced matte paper, 1 of 8 plus 2AP, 59.4 x 42 cm. Acquired 2024

Nonzuzo Gxekwa is a Johannesburg-based photographer whose approach to photography favours the everyday over the spectacular, sharing intimate moments by focusing the camera on subtle gestures and fleeting moments. Whether photographing in the street or in the studio, her work is loving. Gxekwa witnesses the human condition in subtle and beautiful ways that highlight self-discovery and self-expression in the people she depicts.

Johannes Maswanganyi

South African, born 1949

Risimati is Running, n.d. Carved and painted wood.115 x 120 x 52 cm. Acquired 2024

Johannes Maswanganyi was born in 1949 at Msengi Village, near Giyani, Limpopo Province. Although Maswanganyi had no institutional art training, his father taught him to carve traditional and functional items such as utensils and headrests. Maswanganyi soon adopted these traditional artistic forms to urban and international art production. He also became his own dealer and middleman, transporting his work from Msengi to the cities to sell directly to galleries, shops, collectors and dealers.

Maswangenyi’s witty portraits use the pre-existent shapes of tree branches and twigs, often painting them with household enamel paint. This use of paint he learned from fellow Limpopo-based sculptor Dr Phuthuma Seoka.

DuduBloom More

South African, born 1990

Trusting enough to hold myself I - V, 2021. Archival pigment on Felix Schoeller True Fibre, 3 of 5 plus 2 AP, 26 x 21cm. Acquired 2024

Duduzile (DuduBloom) More is a visual artist from Soweto. More’s artworks pose questions around how we confront, acknowledge and heal from trauma. In her textile-based works, obsessively made and with beguiling bright colours, she explores finding ways to manage traumas and triggers.

Ndikhumbule Ngqinambi

South African, born 1977

Figures and dogs in a landscape, 2006. Oil on board, 49 x 86 cm. Acquired 2024

Ndikhumbule Ngqinambi is a self-taught painter whose artworks are inspired by film and theatre. His paintings frequently suggest ancient landscapes and seem to be telling age-old ancestral stories. Ngqinambi’s paintings reflect South African social dynamics and wider political landscapes.

Levy Pooe

South African, born 1994

The Monologue, 2022. Acrylic on canvas, 119 x 84 cm. Acquired 2024

Levy Pooe describes his work as a public social diary. In his art, Pooe aims to make visible moments of contemplation, conversations, daily rituals and routines in everyday South Africa. Pooe is not interested in depicting the exceptional or spectacular but rather creates narratives that speak to the mundane, contemplative and intimate in the urban experience.

Mary Sibande

South African, born 1982

Lead Me On to The Light, 2024. Etching and hand-painting, 4 of 10, 53.5 x 69.7 cm. Acquired 2024

Mary Sibande is a South African sculptor, painter and installation artist whose work interrogates the intersections of race, gender and labour in South Africa while actively rewriting her own family’s legacy of forced domestic work under the Apartheid state.

Sibande employs the human form as a vehicle for her focused critiques of stereotypical depictions of Black women in South Africa. Understanding the body as a site where history is contested and where an artist’s fantasies can play out, Sibande constructs counter-historical narratives in which her alter-ego, a persona by the name of Sophie, is the central protagonist.

Haneem Christian

South African, born 1996

Left to right: The House of Le Cap + Chenal Le Cap + Matte le Cap. From The Memorial Ball (2020). Inkjet print on cotton rag paper, 84 x 60 cm. Acquired 2021

Fortuin was an award-winning dancer/choreographer, a prominent figure in the local ballroom dancing scene, a queer rights activist and the founder and mother figure of The House of le Cap, which is well-known for creating a space for celebration, support and education for the LGBTQI+ community in Cape Town. Pictured through Christian’s striking and solemn portraits are close associates of Fortuin, who were loyal attendees of the nightclub at which Fortuin hosted several memorable balls. The Memorial Ball (2020) shares in the painful loss of a mother figure, as family members celebrate the memory of her grace to reconcile her loss, finding sanctum and joy through queered familial bonds.

For more details, read the think piece Grace, Hope and Gratitude: Celebration and subversion in Haneem Christian’s ode to Kirvan Fortuin written by Jared Leite.

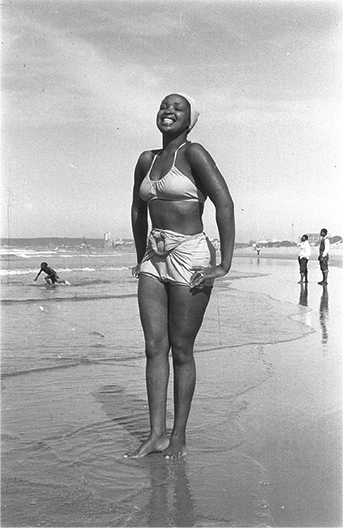

Bob Gosani

South African, 1934–1972

Dolly Rathebe, 1955. Acquired 2021

The photograph of starlet Dolly Rathebe by pioneer Bob Gosani reflects a significant archive of black seaside leisure. This live-giving image hums to the contemporary use of the beachfront, specifically by black people during the festive season, anchoring our place in the history of beach archives. It invites us to listen to a melodious song of black joy, black tenderness, black beauty, black leisure scored by Rathebe’s infectious smile and Gosani’s tender gaze.

For more details, read the think piece Dolly Rathebe photographed by Bob Gosani, at the Durban beach – July 1955 for Drum Magazine written by Luvuyo Equiano Nyawose.

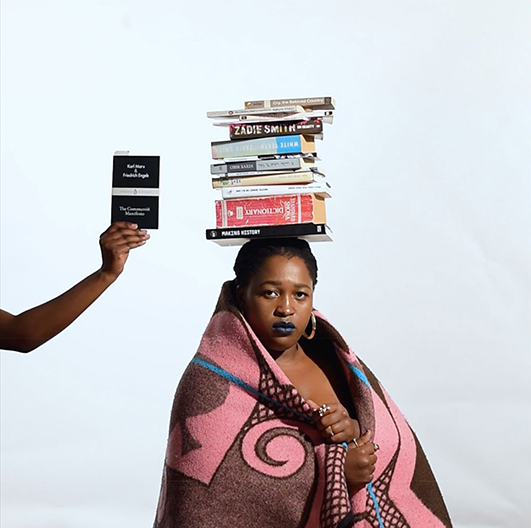

Gerald Machona

Zimbabwean, born 1986

Survive, 2018. Single channel HD video STD 2/5. Duration: 4 min 12 sec, looped. Acquired 2021

Survive raises questions about education, which is seen as guiding path to progress for members of oppressed groups. The books stacked atop Mamabolo's head allude to the teach-ins and political education projects that emerged alongside student protests and performances. "I compared the books of students who participated in the Fallist protest. Books that they were reading at that moment or that they had written themselves. Tankiso then wrapped herself in her traditional Basotho blanket and we stacked all the books on her head while she sang a song about her experience with the academic world in the time of these protests", Machona says of the collaboration.

For more details, read the think piece Gerald Machona: Survive written by Dr Fari Nzinga.

George Pemba

South African, 1912–2001

Portrait of the Barman from Fourways, 1976. Oil on board, 56.5 x 47 cm. Acquired 2021

Seemingly subtle and unprovocative, Portrait of the Barman from Fourways is significant when read through the context of the period it was made. The painting is dated 1976, a year of turmoil and terror when images of the Black body in pain, dead or dying, were circulating globally. Hector Pieterson. Mbuyisa Makhubo. Antoinette Sithole.

For more details, read the think piece George Pemba: Portrait of the Barman from Fourways written by Nkgopoleng Moloi.

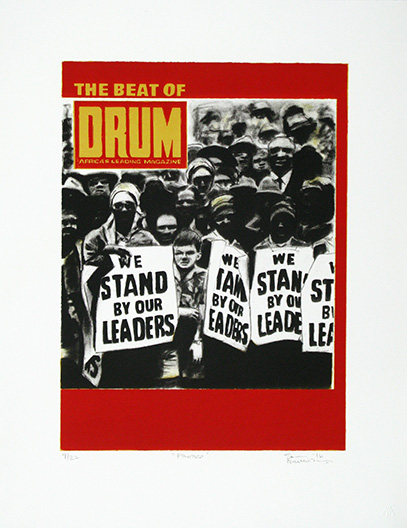

Sam Nhlengethwa

South African, born 1955

Protest, 2016. Lithograph, 12/22, 52.2 x 40.2 cm. Acquired 2020

This is part of a series of prints based on Drum, the famous South African magazine that started in 1951 and which captured the zeitgeist of the 1950s and 1960s. Drum was instrumental in pioneering investigative journalism in apartheid South Africa as well as celebrating life in Black communities. Underlying the images is the narrative of identity and citizenship articulated through dynamic ideas on belonging, equality and universality. With these prints, Nhlengethwa hopes to educate and remind us of where we come from.

For more details, read the think piece Dolly Rathebe photographed by Bob Gosani, at the Durban beach – July 1955 for Drum Magazine written by Luvuyo Equiano Nyawose.

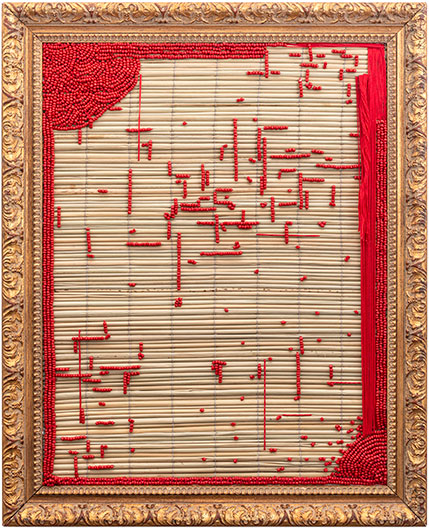

Simphiwe Buthelezi

South African, born 1996

Abadala bayakhuluma (The elders speak), 2019. Straw mat, beadwork in gilded frame, 65 x 53 cm. Acquired 2020

Simphiwe Buthelezi's artistic practice reflects her ongoing interest in the endurance of the female form, sites of blackness, tradition and the gendered gaze in relation to family bonds.

Thero Makepe

Motswana, born 1996

Re A Hlopela (Tombstone Unveiling), 2019. C-type Fuji crystal archival print, 1/10 + 1 AP, 84.1 x 59.4 cm. Acquired 2020

"This body of work is inspired by my grandfather, Hippolytus Mothopeng, who was a jazz musician performing in the 1960s and 1970s in Botswana. Significantly, by the time I was born in 1996, my grandfather had gone blind. He never physically saw me, but we shared a strong bond until he passed away in 2012. One of my grandfather’s dying wishes was for one of his offspring to become a musician, which unfortunately never came to fruition. However, in my practice this year I have aimed to create a sort of visual album for my grandfather, which not only speaks to my family lineage but addresses themes of migration, loss, separation and conflict through my work. At the heart of the conceptual framework for Music from My Good Eye is my family archive, which includes photographs, vinyl records and documentary videos. During my research, what became increasingly apparent to me was the psychological toll that the apartheid regime took on individuals on a micro level, which I had never considered or engaged with before."

Turiya Magadlela

South African, born 1978

Sugar and Spice I, 2019. Cotton and nylon pantyhose, 120 x 120 cm. Acquired 2020

Working primarily with commonly found yet conceptually loaded fabrics, from pantyhose to correctional service uniforms, Turiya Magadlela creates abstract compositions by cutting, stitching, folding and stretching these materials across wooden frames.

Her subject matter moves between articulations of personal experience of woman- and motherhood and narratives from Black South African history. Magadlela tells the story of our complex history in subtle, minimal compositions and engages in a conversation on the colonization of black bodies and women; her art uses materials capitalist in nature at a time when commodification is ever more prescient.

Magadlela studied at the Funda Community College (1998), the University of Johannesburg (1999 –2001) and the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam (2003-2004).

Adolf Tega

Zimbabwean, born 1985

Sithole, 2017. Oil on canvas, 40 x 40 cm. Acquired 2019

The portrait Sithole depicts the artist’s mother, it is a tribute to her strength and dedication.

Asemahle Ntlonti

South African, born 1993

Nonkosiyethu, 2019. Metal, canvas and wool, 179 x 149 cm. Acquired 2019

Ntlonti has become known for her series of handmade textile pieces, referencing traditional blankets worn by the women in her family. These blankets are used to mark significant traditional occasions in the Xhosa culture. Nonkosiyethu (2019) pays tribute to Ntlonti’s mother – each element of the composition carefully selected to represent attributes of her life and experience, from the number of black stripes and tassels to the open selvedge of the fabric. Using canvas instead of wool or acrylic yarn, Ntlonti brings these traditional forms of knowledge firmly into the contemporary space, both in celebration and revision of its power structures.

Ntlonti in a number of works uses the ispeleti (safety pin) and the shawl. She specifically enlarged the safety pin to highlight the role of women.

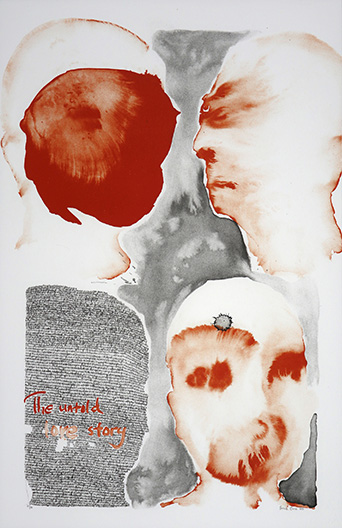

Banele Khoza

liSwati, born 1994

The untold love story, 2018. Two colour lithograph, 11/20, 56 x 36 cm. Acquired 2019

Banele Khoza's lithographs explore a sense of longing and vulnerability. An obsessively neat and detailed text weaves through the print, but often one cannot read all of the words. It is if the artist entices one into his private world and then stops one from fully accessing it, questioning the viewer’s motives for the intrusion.

Khoza’s journals are an integral part of his practice and are reflected in his image-making. Khoza’s interest in the private and the public merges with his interest in social media, technology, connection/disconnection, isolation and a longing to be whole and completely present with someone as well as with oneself.

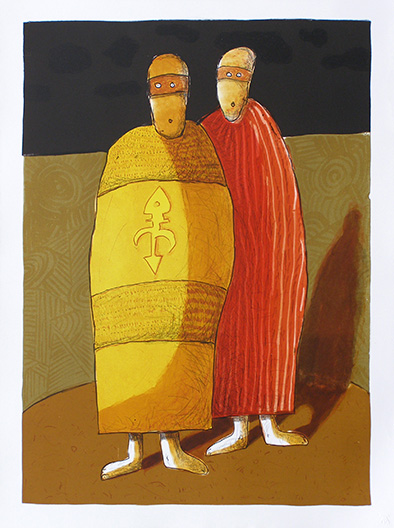

Colbert Mashile

South African, born 1972

Waboraro-ke-mpheane (Three's a crowd), 2010. Eleven colour lithograph, 12/30, 76.8 x 57.7 cm. Acquired 2019

Colbert Mashile has risen to prominence on both national and international level. His work is infused with the natural and mystical elements that are part of his physical and psychological environment. Mashile has an uncanny ability to 'tune into' universal psychological archetypes in his work. These images are completely based on his African identity and yet they link up with the universal. Mashile's fine sense of colour compliments his forms, which seem to celebrate a connection to the earth.

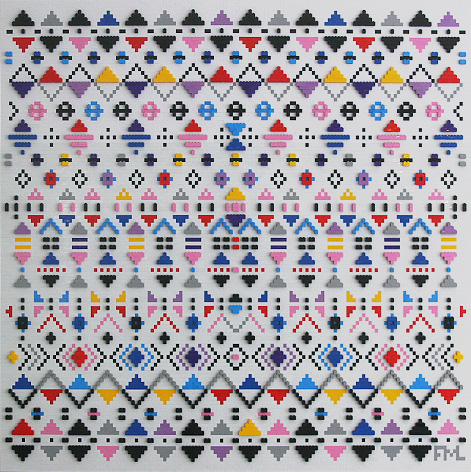

Faatimah Mohamed-Luke

South African, born 1982

Decolourise white, 2018. 9514 pieces of plastic building blocks adhered to Plexiglas, 120 x 120 x 5 cm. Acquired 2019

Mohamed-Luke is a founding partner of the successful designer brand, adam&eve. Having resigned from the fashion industry to focus on art, interior design and working with new materials, her current focus is creating large-scale art made of plastic building blocks. Her

fascination with creating artwork from minute blocks comes from her love of minute detail and intricate patterns. She discovered the art of tessellation, a highly symmetric, edge-to-edge tiling using a simple porcelain shape, on a recent trip to Morocco. She loved

how the surface was painstakingly adorned to perfection and hopes to highlight and recreate the art form with modern materials. This medium creates both nostalgia and relevance while being appreciated by all ages and backgrounds.

Mohamed-Luke holds National Diploma in Fashion (2003) from Cape Technikon, her studies also encompassed graphic, interior, industrial, textile and jewellery design disciplines.

Laura Windvogel (Lady Skollie)

South African, born 1987

We have come to take you home (a Diana Ferrus tribute), 2018. Mixed media on Fabriano paper, 121 x 115.3 cm. Acquired 2019

I've come to take you home (a Diana Ferrus tribute) acknowledges the important role the poem Diana wrote in 1998 played in the official return of Sarah Baartmans body to South Africa. There are many ways of being exiled from your origin. There are many ways of feeling disowned by your own and the physical return of long-dead remains, signal our newfound freedom to return to ourselves, even though we were chased very far. Run back to ourselves, run back to what we thought we forgot. We have come to take ourselves home. To quote Jay Z: "You run this hard just to stay in place. Keep up the pace, baby, keep up the pace. We run this hard just to stay in place."

Lakin Ogunbanwo

Nigerian, born 1987

Untitled IV, 2019. Archival inkjet print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, 1/10 + 2 AP, 150 x 100 cm. Acquired 2019

This work is from the series e wá wo mi (*come look at me) by Nigerian artist Lakin Ogunbanwo. Central to Ogunbanwo’s exploration, are cultures of dresswear in marriage ceremonies. He uses veiled portraiture to document the complexity of multiple cultures and counteracts the West’s monolithic narratives of Africa and women.

Meshach "Shakes" Thembani

South African, born 1975

Untitled, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 120 x 120 cm. Acquired 2019

"In my work, I pay tribute to the hard workers in our society: solo parents, breadwinners and church-goers. I often depict uniformed groups with their accordant dress code symbolic of equality, dignity and solidarity. I use a deliberate stylised technique of bold, flat colour on canvas in a minimalistic palette to portray human figures recognisable by their group identity rather than their individual characteristics."

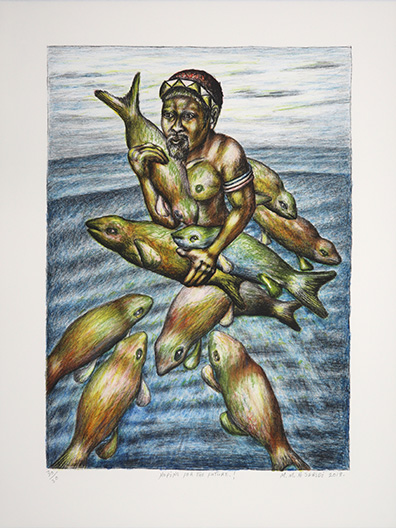

Mmakgabo Mmapula Mmangankato Helen Sebidi

South African, born 1943

Hoping for the future, 2018. Seven colour lithograph, 3/30, 66.5 x 50 cm. Acquired 2019

This is one of two prints by Helen Sebidi which reflect on her family’s spirit animal which is the fish. Portia Malatjie, curator and researcher in Art History and Discourse of Art at UCT Michaelis School of Fine Arts, writes of Sebidi’s work: “Deeply concerned with the effects of the removal of spiritual considerations in modern day life, Sebidi at once advocates for continuous spiritual immersiveness, as well as warning of the dangers of loss of tradition.”

In this series of two prints, the human figures interact with the fish that merges the physical and spiritual worlds and realities. A combination of reality and myth, male and female. Looking at the past as a means of hoping for a better future.

Nobukho Nqaba

South African, born 1992

Ndisilwa II, 2016. Giclee print on Hahnemühle, 4/4, 59.4 x 42 cm. Acquired 2019

Nqaba’s work explores the precariousness of home and opportunity. Using checkered plastic bags commonly known as China bags, plain grey blankets and overalls, she points to the fragility, impermanence and inner resolve necessitated by circumstance. Nqaba’s work reflects on personal memories of growing up in an informal settlement in Grabouw and the complexities of migration and labour.

Smangaliso Khumalo

South African, born 1978

Ifa: Lefa Series, 2016. Inkjet print on Hahnemühle, 2/5, 120 x 90 cm. Acquired 2019

"The genesis of my work was to question that ubiquitous colonial conquest. There have been many dialogues pertaining to the polemical issues around this subject of colonialism. My interest was mainly to revisit these issues that have reached impasse

status. I felt that, certainly there is that nominal change within our socio-political and socio-economic milieu in relation to the black subject; that Di Lampedusa principle that “everything must change in order that nothing changes” is in full formation in contemporary society and post-apartheid South Africa. My body of work focuses on all these issues of intersectionality. Having engaged with these

issues of marginalisation as a black man residing in post-apartheid South Africa my work endeavours to bring about visual cues that depict pressure and tension."

Thandiwe Msebenzi

South African, born 1991

Kwaze kubenini, 2016. Photographic print, 2/3, 45.5 x 63.5 cm. Acquired 2019

"The themes I deal with include being silenced, trauma and violence in spaces of comfort. Woven in that is also the strength that women have, which is both internal and external.”

Thanduxolo Ma-awu

South African, born 1981

Emotions, 2019. Oil on canvas, 150 x 100 cm. Acquired 2019

Ma-awu's art revolves around human experiences and how individuals build identities with the changing world. "Everything is always changing, even ourselves. We are never fixed in the same situations and there is always a way out from harsh realities.” His preferred medium is oil on canvas.

Aïda Muluneh

Ethiopian, born 1974

Denkinesh Part One, 2018. Archival digital print, 2/7, 80 x 80 cm. Acquired 2018

InThe World is 9, the artist Aida Muluneh questions life, love, history and whether we can live in this world with full contentment. “I am not seeking answers but asking provocative questions about the life that we live – as people, as nations, as beings.” The title comes from an expression that Muluneh’s grandmother had repeated, in which she stated, “the world is 9, it is never complete and never perfect.”

Aida Muluneh was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 1974 where she currently lives. Aida left the country at a young age and spent an itinerant childhood between Yemen and England. After several years in a boarding school in Cyprus, she finally settled in Sasktchewan, Canada in 1985. In 2000, she graduated with a degree from the Communication Department with a major in Film from Howard University in Washington D.C. After graduation, she worked as a photojournalist at the Washington Post.

Muluneh’s work has has been exhibited internationally and is included in a number of public collections.

Igshaan Adams

South African, born 1982

I was a hidden treasure, then I wanted to be known, 2016. Fabric, fabric paint, metal, beads, rope and tassles, 226 x 220 x 10 cm. Acquired 2018

Adams combines aspects of performance, weaving, sculpture and installation that draw upon his upbringing. His art is an ongoing investigation into hybrid identity, particularly in relation to race and sexuality. Raised by Christian grandparents in a community racially classified as 'coloured' under apartheid legislature, he is an observant but liberal Muslim who occupies a precarious place in his religious community because of his homosexuality. As such, the quiet activism of Adams’s work speaks to his experiences of racial, religious and sexual liminality, while breaking with the strong representational convention found in recent South African art. He uses the material and formal iconographies of Islam and ‘coloured’ culture to develop a more equivocal, phenomenological approach towards these concerns and offer a novel, affective view of cultural hybridity.

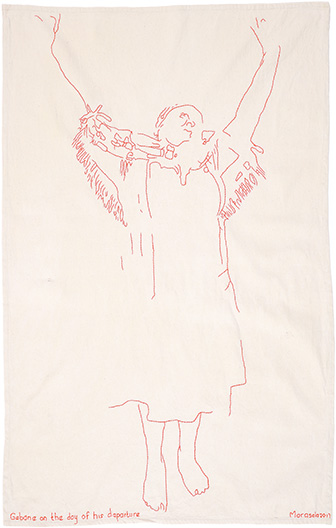

Senzeni Mtwakazi Marasela

South African, born 1977

Waiting for Gebane, 2017. Red cotton thread on K-sheeting, 140 x 90 cm. Acquired 2018

Marasela’s art enters into dialogues with womens’ memories and narratives. She says: "I feel the need personally to participate in writing black womens’ history". Marasela is interested in the multiplicity contained within the experience of waiting: in the pathologies of women who are either forced to wait or choose to wait. In this work, she speaks about this in relation to migrant labour.

For more details, read the think piece Senzeni Marasela's "Waiting for Gebane" written by Sihle Motsa.